Property News

Holiday rentals on the Costa del Sol: What Community Bans Really Mean For House Prices

The October 2024 Supreme Court decision permitted community associations of owners to ban holiday rentals within a community or building. There has been a lot of noise since then, a lot of it ill informed or overblown on all sides. Let’s clear things up.

Prior to the Supreme Court decision, a unanimous vote was required for an association of owners to block holiday rentals. The October decision changed that and it was subsequently codified into law by the national government in April 2025. For communities to ban holiday rentals, they require a quorum of 3/5ths and a 3/5ths majority vote for the ban.

It’s important to state that this does not eliminate those vacation rental properties that were already licensed prior to the law coming into effect. And in communities where there is no vote or there is a vote in favour of permitting holiday rentals, things will continue as normal. Associations can also vote for limitations or to approve on a case-by-case basis.

The complaint – and fear – raised by some in the real estate sector, as well as vacation property homeowners, is that this will make homes in those neighbourhoods less attractive to foreign buyers and investors. The ban will have a downward pressure on prices and on sales velocity – in effect you will have to wait longer to sell for a lower price.

As an article on the real estate platform Idealista argues, two properties in the same community – one with a holiday rental license and one without – will immediately have a price difference of 20%. If they were both previously valued at €1 million, the one with the license is now worth €1.1 million and the one without is worth €900k.

No actual sales evidence is provided for this claim apart from the fact the article refers to an apartment in Marbella somewhere. The Leading Property Agents (LPA) association of real estate agents has argued in a release that was published July 22, 2025 by Malaga Hoy that there were already cancellations or purchases and declines in prices taking place in Marbella.

However, no communities or buildings are named so there’s no way to verify this claim. And prices per square metre continue to rise in Marbella as a whole – up 8.3% last year to €5,213/sq metre, with a 1.0% rise between May-July, after the law went into effect. That suggests no general, downward pressure on sales prices or volume.

That is not to say real life examples do not exist. For example, I know of one development in Puerto Banus which is so popular with holiday rentals that over time it has become an excellent place for investors to park money with a more or less guaranteed yield.

Nonetheless, despite its popularity there existed a majority of residential owners unwilling to rent to tourists. As a result, recently the community voted to ban holiday rentals completely. This means any new owner will not have the right to rent their property for short term holiday rentals.

A local agent informed me personally that this has led to the cancellation of the sale of one or two apartments. Another apartment had to be discounted in order to close a deal since buyers were discounting the loss of future income from the sale.

This would appear solid evidence in favour of the argument the ban on holiday rentals will affect house prices negatively. However, I would argue a few examples are not sufficient evidence and secondly the data pool is not representative of the market as a whole.

The New York Experience

Spain isn’t the first place that has moved to regulate and/or ban Airbnbs. New York and parts of California have also moved aggressively in this direction. In New York, there are strict regulations and strong enforcement that have reduced the number of tourist rentals in the city by 90%

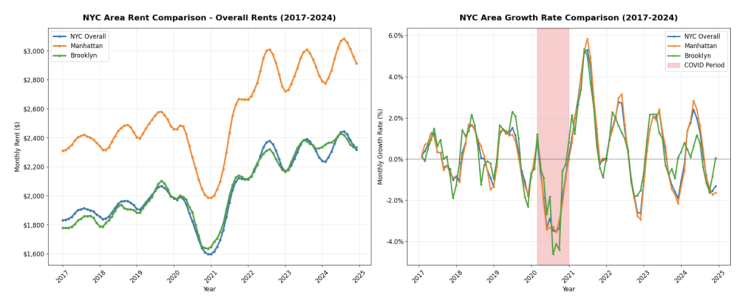

According to a Wall Street Journal article and research articles on Apartment List, a website similar to Airbnb but for long term tenants and apartments, the ban has had no impact on prices or supply. The following charts based upon Apartment List’s numbers below shows this clearly.

There is the market distortion caused by Covid, followed by the exact same pricing patterns afterwards, including after the implementation of the new laws on Airbnb rentals in the city.

A few objections are worth noting. First some claim that not enough time has passed for the full impact to make its way into the market. Secondly, the original number of legal Airbnb’s in New York was relatively marginal – at 38,000 vs 1,000,000 total rental units. Finally, the one definite positive impact that the restrictions can be said to have caused are fewer noise complaints.

Beyond New York, there have been mixed results with some moderately lower rents in Irvine, California after tight regulations were implemented. However, the statistics gathered overlapped with Covid, during which rents fell in cities around the world. That was true in Spain as well.

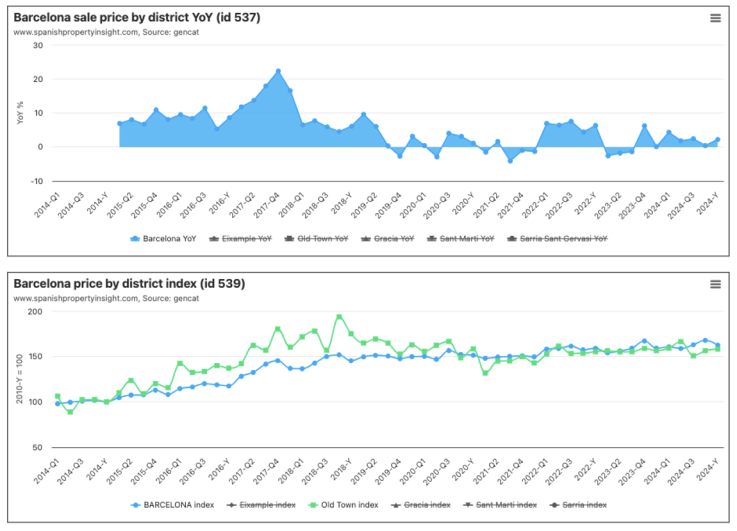

In Barcelona there has been evidence of rental price declines, though it’s a complicated picture because of former tourist rentals shifting to seasonal rentals to avoid rent controls. Those don’t get counted in the long term rent price numbers.

This is a phenomenon happening in other parts of Spain as well, with landlords seeking to avoid rent controls in the face of high housing price inflation that is largely the result of a lack of new construction.

In terms of the impact of regulation and bans on short term rentals (STR), the picture in Barcelona suggests that the tightening may have had a delayed impact on the rate of price increase. That is, prices continue to rise but at a lower rate than they were in 2014-2018. That is visible in these graphs from Spanish Property Insight.

However, even here we can’t conclusively determine the cause of this slowing. In 2014 Spain was just emerging from the depths of a property crisis that saw house prices collapse by 37% over a period of six years. The apparent surge in prices could easily be the result of the return of expansion and the release of pent-up demand.

The only clear conclusion that can be drawn is that removing tourist rentals does nothing to counter the real, underlying problem in cities like New York, Barcelona or Malaga: the lack of construction of rental housing. Vacancy rates in New York, according to the WSJ, remain at historically low levels despite the ban.

The only sector that seems to have definitely benefited has been New York hotels, which have seen significant price rises since 2023. According to the WSJ:

“The average rate for a New York City hotel room rose to $283 a night in July, a 7% jump from two years ago. Occupancy has outpaced 2023 levels every month this year except for July, according to CoStar. The city’s program of paying for tens of thousands of migrants to stay in hotels contributed to the higher occupancy.”

A tale of two markets

I would argue that the character of the new law is a response to a very specific market phenomenon born out of the likes of AirBnB, Booking.com et al. This is the industrialisation of private holiday rentals by individual and company investors. And I would contrast that with individuals who rent out rooms or apartments in their homes for supplemental income.

The former are people or companies buying multiple apartments, mainly in city centres or in high density tourist locations solely for the sake of investment yields. Such practices have created price bubbles, forced locals out of city centres and created friction with residents. According to one research paper, areas with the highest density of Airbnb style rentals experienced a sale price increase up to 19%. As I wrote back in summer, 2023:

“In Malaga, 74% of listings are by companies and people with multiple properties. Around half a dozen companies have more than 50 properties, and one has 178 listings. In Barcelona, the number of multi-listing “Airbnb hosts” is 71%, with one company alone having 241 listings!”

While it seems dubious that targeting these investors will increase the housing supply or reduce rents substantially, they should nonetheless be treated and regulated as tourist businesses, like hotels.

The Tyranny of the Majority

However, applying a blanket law to all Airbnb properties is a blunt weapon and there are casualties amongst those who haven’t skirted regulations or created so-called “ghost hotels” spread across dozens of properties.

These are the individual homeowners who either want to make a little extra money from a spare room – or who help to cover the annual costs on their vacation home by renting it when they aren’t there.

Such owner-landlords have an interest in preventing wild parties happening in their homes, both to prevent damage to their own property and to stay on good terms with their neighbours, whom they will have to see in the elevator or communal pool. Banning them from occasional rentals in their own homes amounts to a denial of their right to enjoy their home – rather than regulating a large scale commercial enterprise.

What is ironic is that those with vacation homes are actually taxed as though they are renting it out, whether they are doing so or not – including whether they are banned from doing so or not. That suggests that the law needs finessing in order to address these different types of holiday renters.

That could mean, for instance, setting limits on the number of days per year when a property can be rented out or a rental cap on the % of rental licenses in a given community. Such measures discourage investor-landlords, who have no incentive to purchase properties that can only be rented a portion of the year. But it permits owners who want to supplement their income by taking advantage of times when they aren’t in the unit or during festivals, etc.

The effect on Property Prices

Back to the effect on property values of the law as it currently stands. It is too early to know for certain what the effects will be. Secondary effects from legal changes can take some time to show up. The current market also remains strong, based on fundamentals that aren’t going to change overnight.

But we shouldn’t wait until things go badly wrong to fix them – an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as they say. We can see the possible negatives already. And we know that there are different types of Airbnb users, who should be treated differently by their communities.

The government should be making ongoing revisions to the law to make it a tool that improves things. We don’t need a law that adds more difficulties for another group of people – on top of those that exist because of a lack of affordable housing.

By Adam Neale | Property News | September 23rd, 2025

Related Posts